The work Landing Sites, undertaken in the context of a practice-based PhD at the Film University Babelsberg KONRAD WOLF (Potsdam, Germany), takes the form of a real-time “film” shot from within the simulation engine Microsoft Flight Simulator 2020. Drawing on a lineage of artistic works dealing with temporality and environment such as Nancy Holt’s Sun Tunnels and James Benning’s 13 Lakes, the work seeks not only to engage critically with these traditions, but furthermore to articulate the current relationship between the politics and aesthetics of whole earth simulations, as found in media such as video games, climate simulations, and digital cartography. Generated in real-time rather than pre-recorded in order to make use of the engine’s real-time weather and day/night cycles, the film cuts metrically within the simulation between a series of sculptural works integrated as dynamic scenes within the simulator. In this way, the film seeks not only to articulate the relationship between the categories of “local” and “global” within the simulator, but furthermore to bring into confrontation notions of planetary, cinematic, and computational time that find expression in the software.

Planetary, computation, simulation, real-time, land art, aesthetics.

Since the 1960s, artists and film-makers have sought to articulate through various media the shifting relationship between the human subject and the planet. The last 20 years in particular have seen the rise of computational media not only in artistic practices but also as a means to represent the planet in real-time in media such as traffic simulators, climate simulations, global web map services, and “Digital Twins”. Such real-time planetary representations occupy a increasingly important space in the media landscape of the 21st century and therefore play a growing role in restructuring temporality and environment in the public consciousness. There is arguably therefore an artistic responsibility to respond to these socio-technological developments and articulate the changing relationship between these categories.

Beginning with the US-launched Explorer 6 in 1959, the first satellites intended for monitoring earth’s terrestrial environments and atmosphere began to be sent into orbit, eventually allowing a new image of the entirety of the earth’s surface to be produced every few months. This god-like view from above, decoupled from the horizon that had characterised depictions of landscape since the mediaeval period (Steyerl 2011), has become an enduring motif of subsequent environmental movements (Heise 2008). Two of the most widely-circulated images during this period were ones in which the whole earth was photographed — for the first time — as a single static object, floating in a void. First Earthrise, taken by astronaut William Anders in 1968, then Blue Marble, taken by the crew of Apollo 17 in 1972, rendered the planet as a “mythical garden” (Bratton 2019, 15) in which the human subject became subsumed within the global village.

The aesthetics of satellite imagery were key to the development of artistic movements at the time, perhaps most notably the Land Art movement of the 1960s onwards. Anchored principally in the environmentalist imagination of the western USA, the movement gave rise to a number of figures that managed to articulate this moment of raw technological ambition, environmental angst, and (American) economic hegemony. Among these, Nancy Holt is one of the best known due to her work Sun Tunnels (1973 - 76, Fig. 1), in which she oriented large concrete cylinders along two axes corresponding to the rising of the sun on the winter and summer solstices.

Fig. 1. Nancy Holt’s Sun Tunnels, Great Basin Desert, Utah (1973 - 1976). (© Holt/Smithson Foundation)

Like many works of land art, Sun Tunnels sought to articulate the relationship between the conditions of the site and those of the planet, in this case through the creation of a site-specific work that can only be made sense of through reference to the rotation of the planet on its axis. While the work may only be activated according to the cyclical time of the diurnal and seasonal cycles, the sculptures themselves serve to fix this relationship in chronology, and thus in the register of linear time.

If Sun Tunnels materialised this relationship in sculptural form, moving image works have sought to bring into confrontation their own notion of time with that of the planetary. In James Benning’s 13 Lakes (2004, Fig. 2), for example, the audience is presented with a series of 10-minute static shots of 13 lakes across the USA. Through the use of long sustained shots of landscapes, a cinematic language that Benning has developed throughout his career and that finds a home within a broader cinema of stasis (Remes 2015), the role of montage in shaping the flow of time in film is pushed to the background in favour of an unfolding of events in their own time. In the process, he takes the notion of the “time image” (Deleuze 1985) to an extreme, where the mediating agency of the camera nearly falls away completely and we are left with a heightened sense of realism. The cutting together of 13 such scenes nonetheless reaffirms the “mapping impulse” of the film (Castro 2009), which ultimately subsumes the time of events within the narrative time of cinema.

With the increasing use of computer simulations within artistic and film-making practices, a new dominant logic of “real-time” emerges to contend with cyclical and linear time. In David Claerbout’s work Olympia (2016, Fig. 3), the slow decay of the Berlin Olympic Stadium over 1000 years is modelled according to real-time weather data that is loaded and simulated within the simulation. The work, which began in 2016, is provisionally scheduled to run until 3016 when the simulated Olympic Stadium will have supposedly reached its final state of decay. Until then, in theory, every second will be depicted within the simulation. Such durational real-time media, which represent perhaps one logical endpoint of durational film projects like Benning’s, map both the cyclical time of diurnal and seasonal cycles and linear time of chronology onto “real-time”, which seeks an ever-more-accurate and up-to-date representation of the present moment1.

Fig. 2. Still from James Benning’s 13 Lakes (2004). (© James Benning)

Fig. 3. Still from David Claerbout’s Olympia (2016). (© David Claerbout)

By focusing on the three artistic works outlined above, I intend to sketch a lineage of works that serve as conversation partners for the project described below. All three works articulate not only a relationship between temporality and environment through their specific medium (sculpture, film, and simulation), but also a chronology of mediation beginning in the 1970s and continuing through to the 21st century. As such, they become representatives of a certain aesthetic of temporality and environment that existed at the historical moment of their creation. In the next section, therefore, I turn to an example of a current media object and ask what kinds of aesthetics it embodies.

The past 20 years have seen an increasing prevalence in the media landscape of real-time representations of the planet. One important recent example of this phenomenon is the role-playing simulation Microsoft Flight Simulator 2020 (MSFS). At the core of this flight simulator is a real-time representation of the entire planet, which serves as a field of play for virtual pilots. Beyond being a 3D visualisation, however, the simulator also includes a day/night cycle, weather engine, and flight plans that draw in real-time data from APIs and sensors around the world and visualise them within the simulation.

A basic understanding of how this software constructs the world acts as an introduction to its politics. The visual model of the planet is the work of an AI start-up, Blackshark.ai, and the space technologies company Maxar. Maxar’s “Worldview Legion” satellites — their models for earth observation — claim to image up to 5 million square kilometres of the earth’s surface per day, and use this imagery to create 3D models of the planet that are used by mapping services such as Google and Apple maps, as well as by clients in the military, entertainment, and disaster relief (MAXAR 2024). Blackshark.ai are, by contrast, primarily a video game company specialising in open world games. For MSFS, the company developed image-segmentation algorithms to identify buildings and vegetation within Maxar’s imagery and procedurally generate buildings in 3D according to these footprints (Blackshark.ai 2024). For the live air traffic, the simulation uses the FlightAware API, which tracks Automatic Dependent Surveillance–Broadcast (ADS-B) signals from aircraft around the world (Haroon 2020). For weather, meteoblue live weather reports are used to provide semi-real-time meteorological updates around the world. These reports are then visualised within the simulation using the internal weather engine (Schloegi 2023).

This merging of the planet and its real-time image has political implications. If satellite imagery renders the earth’s surface as a 2D canvas, media such as MSFS render this canvas as a field of action. While the image of the earth drawn upon by the land artists was a static rendering of a timeless geological object viewed from space — an image that has been heavily criticised by members of Native American communities (e.g. Asenap 2022), as well as from a post-colonial perspective in the academy (e.g. Harris 2020) — the image of the earth proposed by by MSFS creates a hierarchy out of those those systems that move in real-time (weather, the sun, air traffic, water traffic), and those that seem fixed outside this regime (people, the landscape, vegetation). The result is a function of the computational infrastructure that produces the simulation, where the availability of real-time data becomes the marker of inclusion/exclusion from the world image.

Landing Sites is conceived as a real-time “film” shot within the MSFS engine with the aim of articulating the current relationship between the politics and aesthetics of the real-time earth image — particularly that found within the flight simulator — while critically engaging with the legacy of former aesthetic movements that dealt with similar themes.

The “film” is composed of a series of 24 shots, each lasting 60 seconds and between which the camera cuts randomly. Each shot focuses on a sculptural installation placed at a certain location on the simulated planet. The placement of the sculptures corresponds to the 24 standard meridians, which transect the planetary surface every 15 degrees of longitude and provide the basis for the time zones. In this way, their placement makes a reference to a tradition of meridian markers, which often take the form of sculptures commissioned by local communities and used to mark where a meridian line passes through a certain point (e.g. a town, a local park).

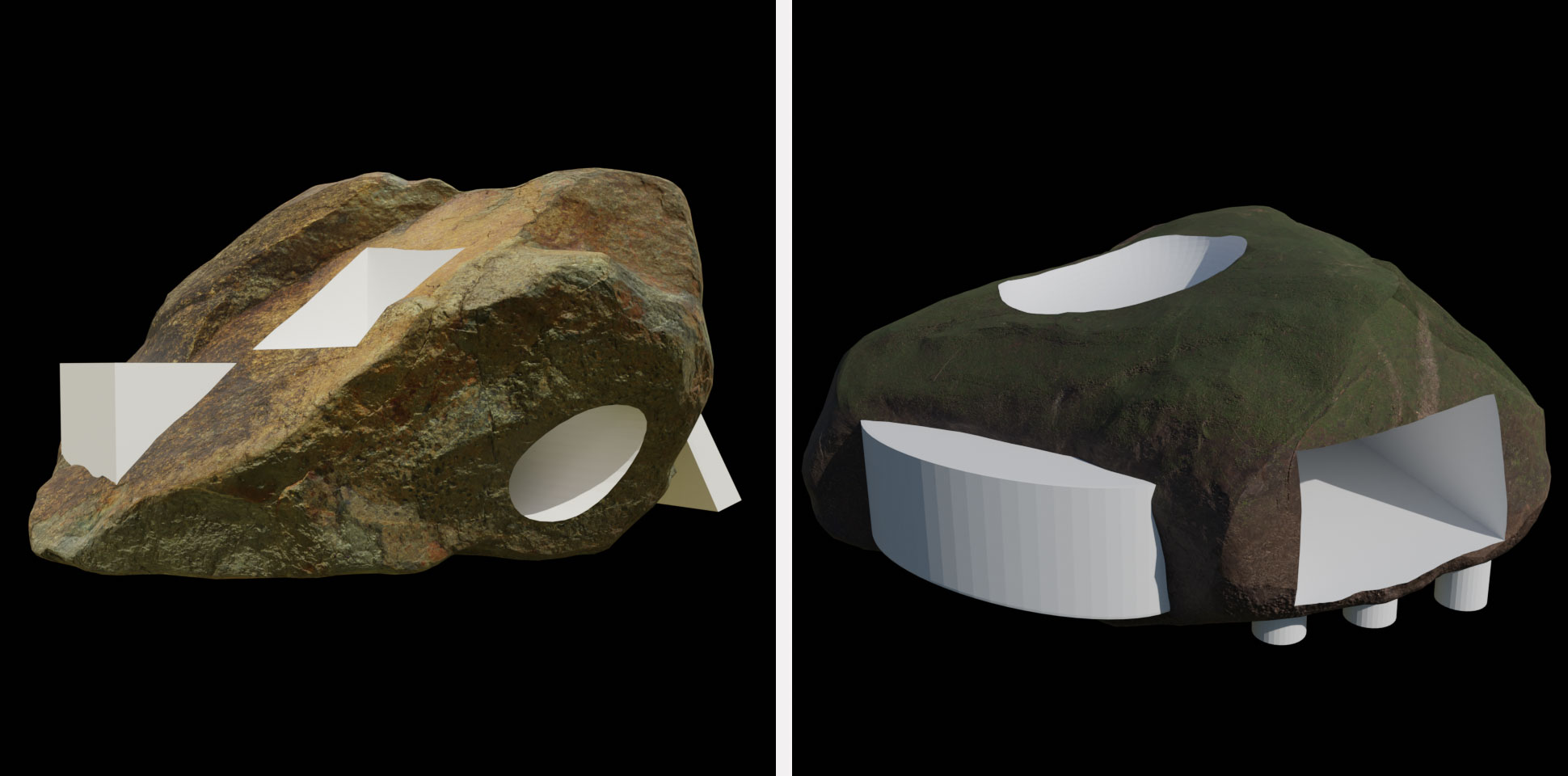

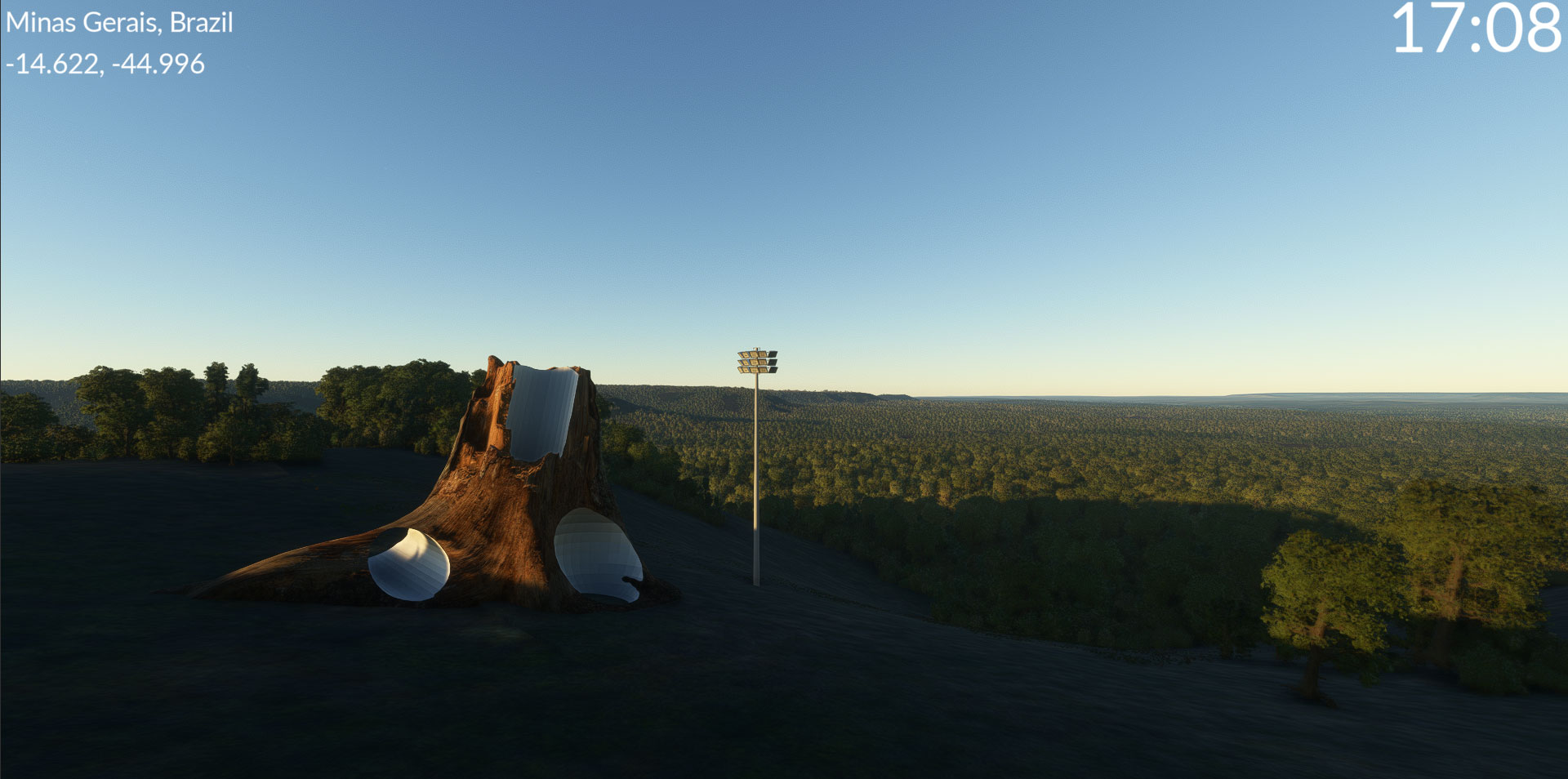

The sculptures themselves take the form of photogrammetry-scanned natural objects (e.g. rocks, fallen trees) taken from an online asset store and augmented with blocky architectural forms (see Fig. 4). While in part building on previous digital sculptural works of mine, Tirana Time Capsules (Walmsley, 2021), the sculptural language further seeks to articulate a relationship between the local (with its connotations of uniqueness) and the global (with its connotations of universality), in this case through the prosthesis of primitive shapes (e.g. cubes, cylinders, spheres) onto idiosyncratic ones (e.g. the scans of individual rocks). The result is in essence a series of architectural follies, which may on first glance be mistaken for utilitarian structures such as airport terminals, but in fact serve no function at all.

Fig. 4 3D-renders of two of the sculptures to be placed in the simulator.

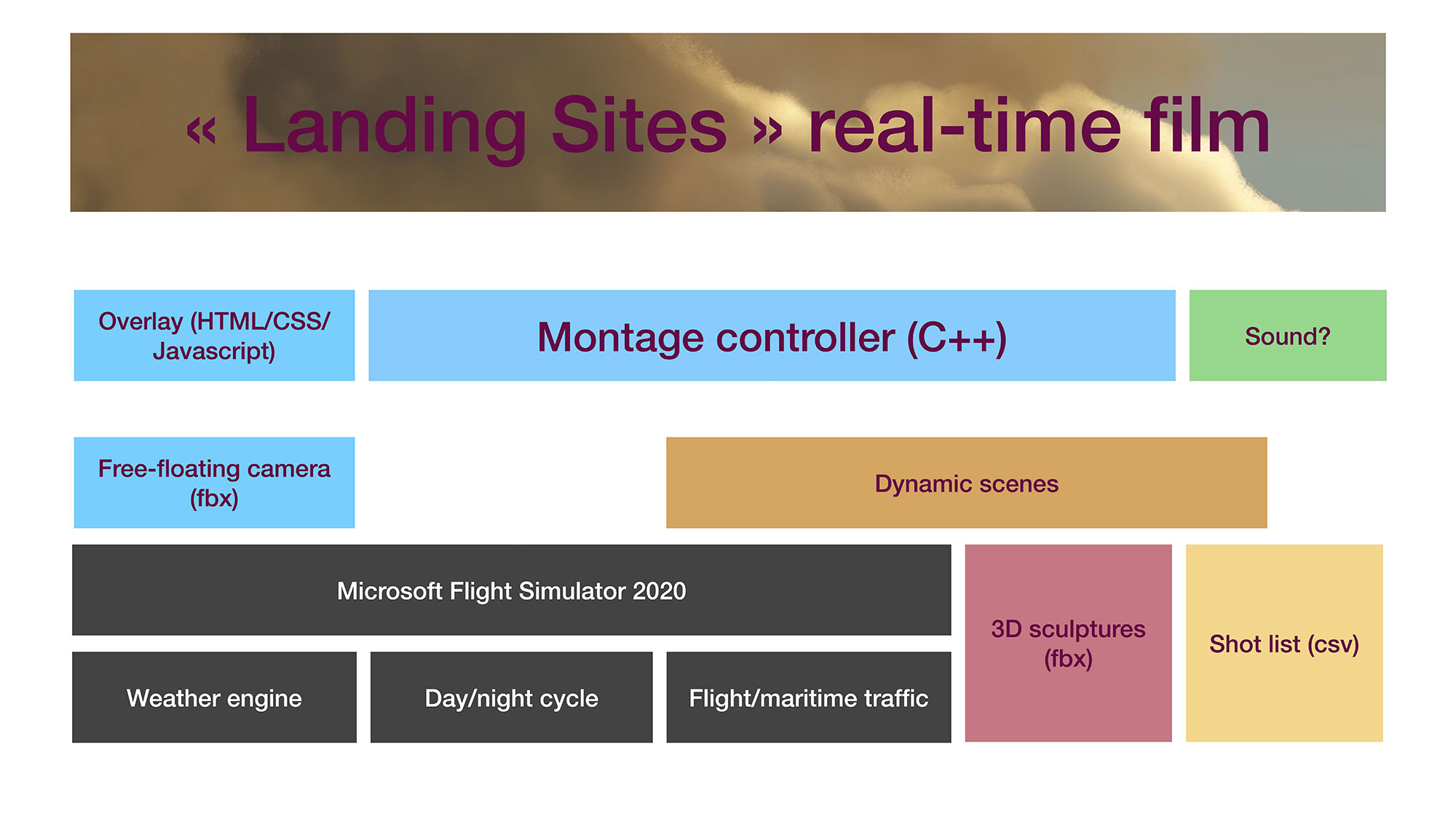

The software stack diagram below (Fig. 5) illustrates the main components of the work:

MSFS Engine: The engine itself, built by Microsoft and Asobo Studios, which generates the graphics and physics in real-time. In addition, the engine draws in data from APIs in order to generate accurate real-time air and water traffic, as well as weather.

Free-floating camera: A custom virtual camera system for the MSFS engine that allows a camera to be free-floating, rather than always attached to an aircraft (the default in the simulator).

Shot list: A csv file containing the metadata for each camera shot in the film. The shot list contains the latitude, longitude and altitude for each shot, as well as the pitch, roll, and rotation of the camera.

Montage controller: A custom C++ script that communicates with the simulator in order to take control of the virtual camera and make it cut every 60 seconds to any location on the shot list (see Fig. 6).

Overlay: A simple interface using HTML and CSS that displays a short text string as well as the latitude/longitude and local time of the location where the camera has been placed in the simulation (see Fig. 6).

Sculptures: A series of digital 3D sculptures, installed at different locations on the virtual Earth. They are then augmented through dynamic elements that react to real-time weather and lighting conditions.

Sound: Although sound will eventually play a role, the work currently has no sound design. This represents an area of ongoing research and experimentation, and will be one focus of work over the coming months.

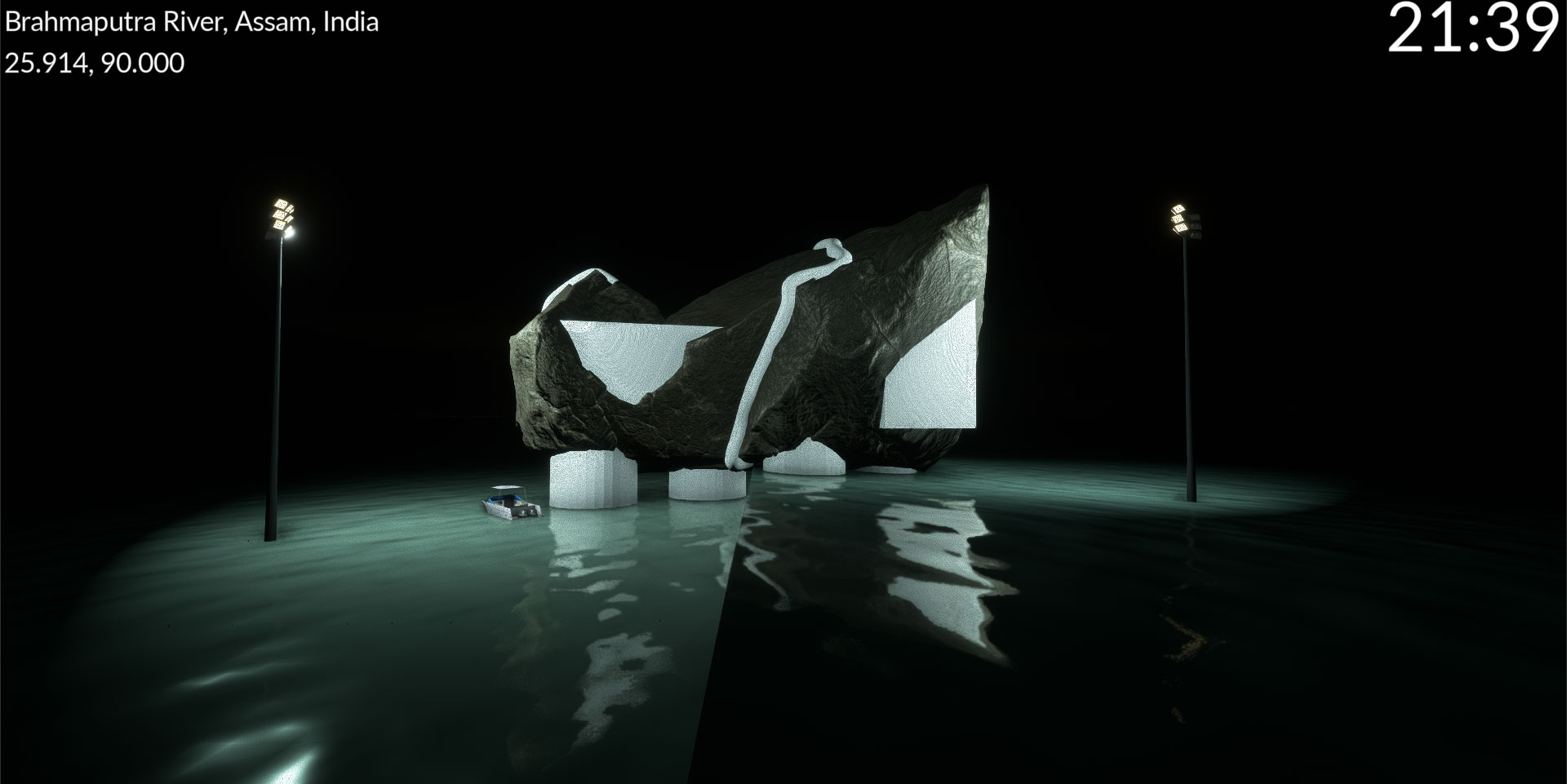

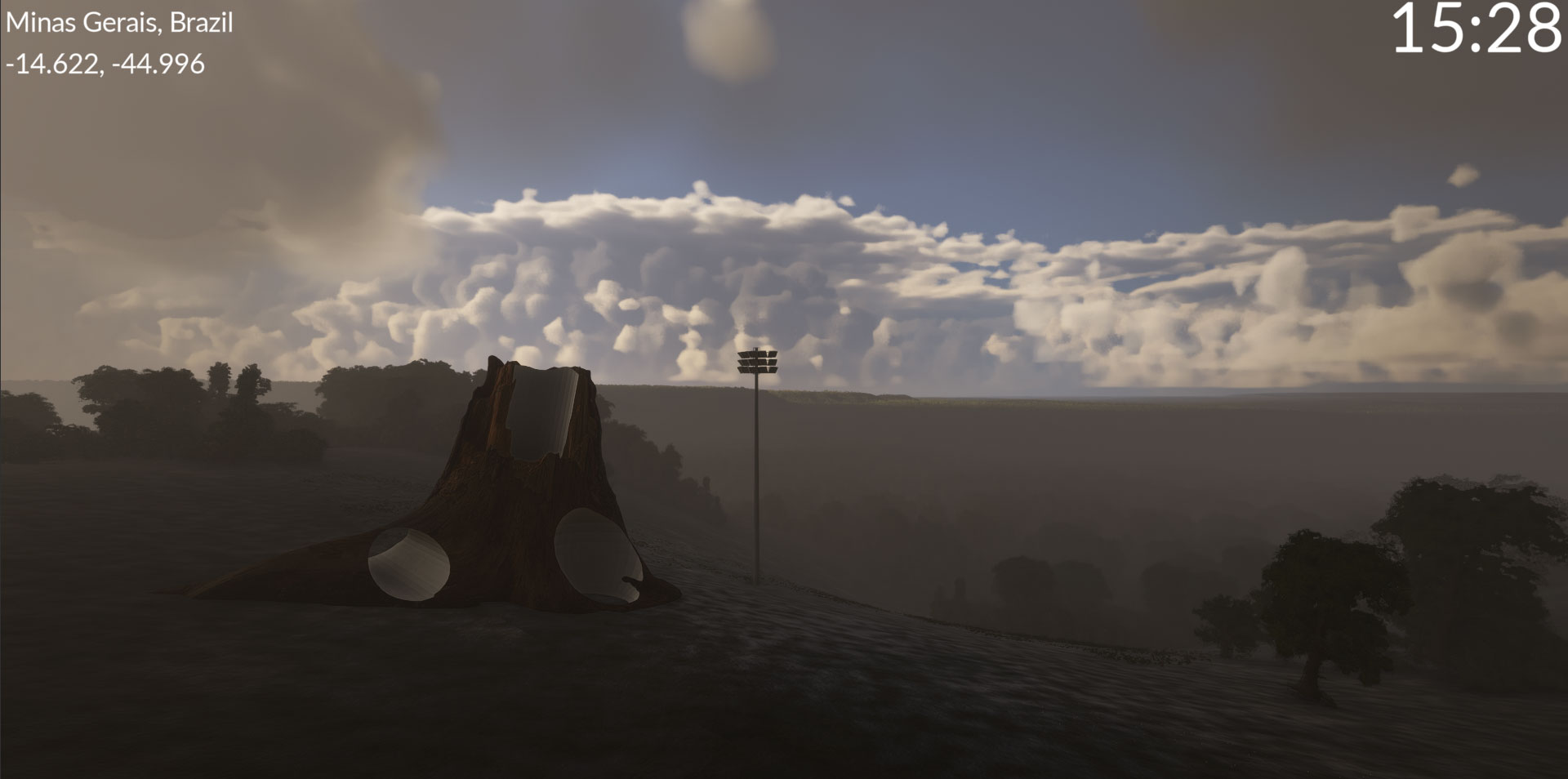

Fig. 5 Software stack diagram for Landing Sites

The film relies on the capabilities of the MSFS 2020 engine to simulate real-time weather conditions and the local time at each depicted site. The dramaturgy of the film therefore evolves over time through the interplay between the metric montage of the shots, the sculptural installations, and the real-time conditions of each site. Due the nature of the film being rendered in real-time, rather than pre-recorded, it is in essence a different film every time it is encountered by an audience, depending on the time of day, year, and weather conditions. It is therefore also durational, having no fixed starting point nor end point, and no fixed running time.

It is for these reasons that the word “film” is used somewhat provocatively to describe the work. Although formally presented as a film, it is in its technical construction a simulation. It is, however, perhaps better thought of as a timepiece that seeks to articulate a relationship between planetary time, cinematic time, and computational time. Its ideal presentation would be on a single channel screen, permanently installed in a public space where people are in transit (e.g. a shop window on a busy street, a train station, a hallway in a building). It is in such a situation that the work is able to function almost as a clock: inviting not sustained but rather fleeting attention, encountered briefly once or multiple times per day and over the course of many months, in order to accompany the flow of daily and seasonal activities in the space.

Fig. 6 Selected stills from prototype of Landing Sites

Asenap, Jason. 2022. “The Problem with Land Art” Alta Online. December 21. https://www.altaonline.com/culture/art/a42042641/land-art-jason-asenap/

Blackshark.ai. n.d. “Synthetic 3D Globe.” Accessed 22 January 2024. https://blackshark.ai/#Synthetic3DGlobe.

Bratton, Benjamin. 2019. The Terraforming. Strelka Press.

Castro, Teresa. 2009. “Cinema’s Mapping Impulse: Questioning Visual Culture.” The Cartographic Journal 46 (1): 9-15. https://doi.org/10.1179/000870409X415598.

Deleuze, Gilles. 1985. L’image-temps. Cinema 2. Les Editions de Minuit.

Harris, Alicia. 2020. Homescapes: Indigenous Land Art and Public Memory. PhD Dissertation, University of Oklahoma.

Haroon, Henna. 2020. “Announcing FlightAware and Microsoft Flight Simulator Partnership”. FlightAware, last updated 1 July 2020. https://www.flightaware.com/news/article/Announcing-FlightAware-and-Microsoft-Flight-Simulator-Partnership/1477.

Heise, Ursula. 2008. Sense of Place and Sense of Planet. The Environmental Imagination of the Global. Oxford University Press.

MAXAR. n.d. “It Takes A Legion.” Accessed 22 January 2024. https://www.maxar.com/splash/it-takes-a-legion.

Remes, Justin. 2015. Motion(less) Pictures. The Cinema of Stasis. University of Columbia Press.

Schloegi, Michael. 2023. “meteoblue live weather data in Microsoft Flight Simulator” Meteoblue, last updated 26 June 2023. https://www.meteoblue.com/en/blog/article/show/40088_meteoblue+live+weather+data+in+Microsoft+Flight+Simulator

Steyerl, Hito. 2011. “In Free Fall: A Thought Experiment on Vertical Perspective.” e-flux journal 24.

Virilio, Paul. 2000. Polar Inertia. SAGE Publication.

Virilio, Paul. 2013. “The Illusions of Zero Time.” In Virilio and Visual Culture. edited by John Armitage and Ryan Bishop, 28-36. Edinburgh University Press.

Artworks cited

Holt, Nancy. Sun Tunnels. 1973-1976. Site-specific sculpture.

Benning, James. 13 Lakes. 2004. Film. Running time 133 minutes.

Claerbout, David. Olympia. 2016. Real-time simulation.

Walmsley, Alexander. Tirana Time Capsules. 2021. Virtual environment and 3D digital sculptures.

Bio

Alexander Walmsley (he/him, b. 1992) is an artist and researcher. His recent work has been exhibited at the 59th Venice Biennale, the Daejeon Biennale of Arts and Sciences, the Sharjah Art Foundation, The Photographers’ Gallery and Ars Electronica and was shortlisted for the Deloitte Photo Grant in 2023. He is currently a lecturer at the Film University Babelsberg KONRAD WOLF, where is also pursuing a practice-based PhD. He holds previous degrees in Anthropology and Archaeology from the University of Cambridge (UK) and the University of Geneva (CH).

A deeper discussion of this mode of temporality has been discussed elsewhere (e.g. Virilio 2000, 2013), but is not the focus of this paper.↩︎