“First Contact” is a PhD research aimed at exploring the minimal information required for humans to understand and engage with non-human entities, social robots and virtual shapes, through non-verbal communication, focusing on creating authentic, believable, and socially interactive characters. Subjects unknowingly interact with each other through a digital filter that transforms their bodies into new creatures that the other will interact with, creating a context to test genuine understanding of this alien otherness. The project takes the form of two projects, “The Game” and “The Room”, experimenting with radically non-anthropomorphic bodies with different narratives and interaction contexts.

Digital Art, Robotics, Virtual Reality, Animacy, Human-Computer Interaction, Embodiment, Non-verbal communication.

Hugh Herr believes that in the 21st century humans might extend their bodies into non- anthropomorphic forms, like wings, and control and feel these movements through their nervous system, drastically changing our morphology and dynamics [4]. This concept raises questions about the nature of our bodies, identity, and potential virtual existences. Avatars are crucial in shaping our social lives and identities, as they become the means through which we embody and express ourselves [7].

My PhD research investigates the challenges of embodiment and genuine human interaction with non- anthropomorphic beings (in terms of shape, perception and expressive capabilities), using only non-verbal communication. By imbuing these entities with unique narratives, motivations, and desires, the study seeks to create truly authentic and relatable characters.

This study challenges traditional notions of what constitutes a living and social body, leveraging new technologies to expand our understanding of embodiment and cognition. As the concept of embodying avatars different from human morphology is gaining attention [2, 3, 6], this research investigates how far we can push the level of non-anthropomorphism while still retaining the possibility to understand the world and act in it through the avatar. Research on embodied cognition [1, 5, 8, 9] emphasizes the body's central role in processing and understanding reality, while also showing the human’s capacity to re-adapt to different body morphologies, a phenomenon called homuncular flexibly [12]. Thus, exploring radically altered bodies can help us surpass our current understanding of cognition.

At the same time, this research aims to determine what makes a non-human entity appear "alive" to humans by examining the physical elements, movements, sounds, and actions that contribute to this perception. This aim is shared with social psychology research, such as the famous Heider and Simmel test on social intelligence [10], where they showed that humans could attribute human-like behavior and motivations even to simple geometrical shapes, and the entire field of animation, starting from Disney’s “the illusion of life” showing the principles that could make a drawing of a half- empty sack of flour display emotions. Applications of this research range from social robotics [11] to creating more relatable and empathetic characters in entertainment. The project aims at offering insights and guidelines into the development of realistic non-humanoid social creatures and their impact on human-technology engagement in an increasingly digital world.

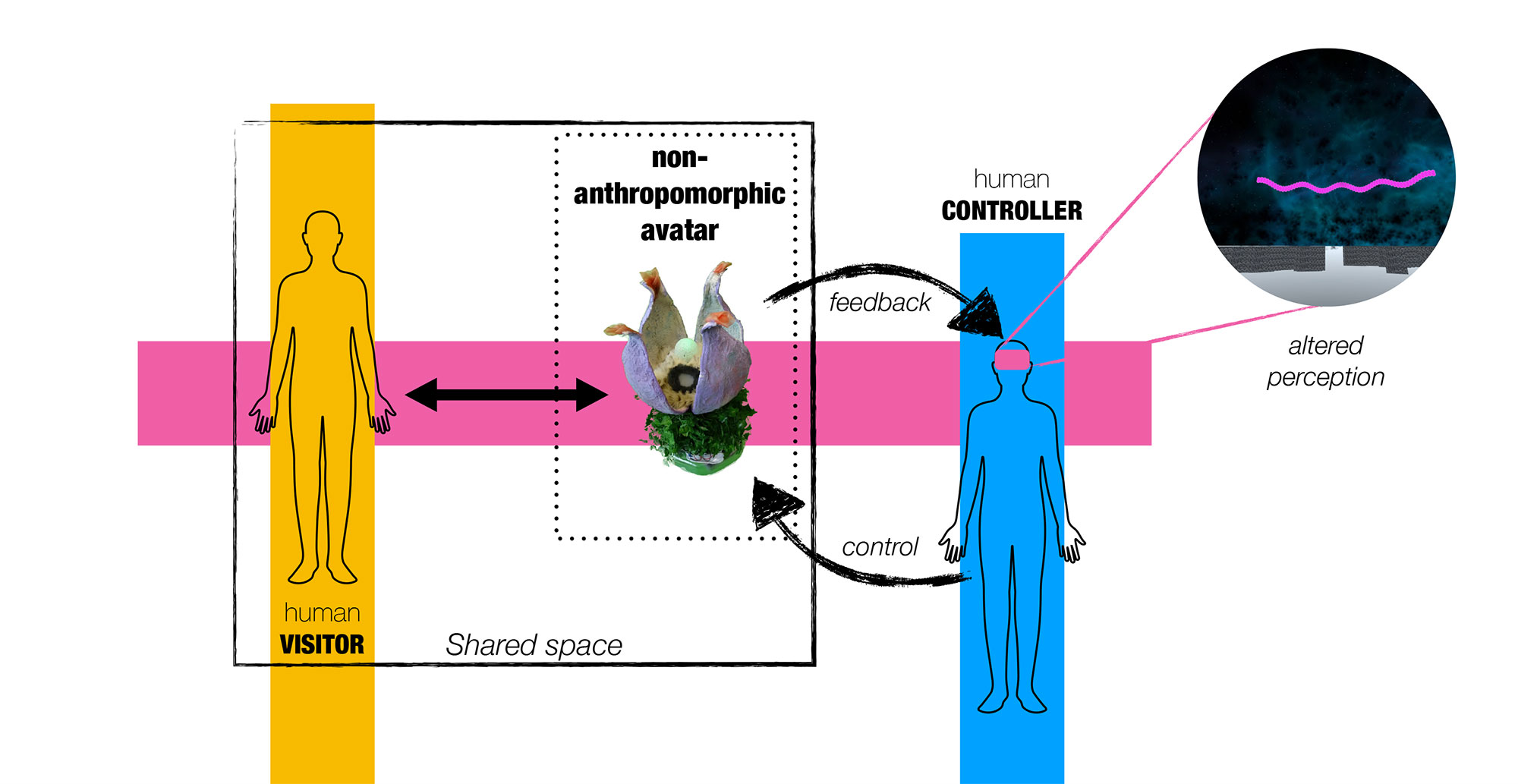

Both projects depend on a 'digital filter' -- a mechanism that allows participants to interact while concealing their identities (Fig. 1). One human acts as the Controller. The other human acts as 'the Visitor'. The Controller embodies the avatar and controls the avatar by using embodied controllers. The Controller perceives reality in an altered way with a VR headset. The visual information the Controller perceives is a translation of data received by the avatar’s sensors in real-time. The representations the Controller sees are abstract. The human Visitor seen by the Controller is not a recognizable human entity. Meanwhile, the Visitor interacts with this non- anthropomorphic avatar.

Fig. 1. The Digital Filter diagram. Visitor subject and avatar interact directly in the same shared space. The Controller embodies the avatar and perceives reality through it with an altered representation

These two entities, Controller and Visitor, are in direct interaction within the same shared space, but act through the digital filter described above. Crucially, the two can’t speak. They can only communicate through the motion of their digitally filtered bodies. Neither is able to perceive another human directly. Instead, they are each 'the other' human 'translated' into an alien presence.

Both instances can be considered "first contact" between two beings that don't know or understand each other at first, with non-anthropomorphic bodies, that need to find a way to learn how to communicate non-verbally to achieve some sort of objective.

The contribution of this paper is the following: to introduce the First Contact research, outlined into its two tracks (The Game and The Room), with preliminary results of the pilot studies that were performed.

The research is divided into two main projects, each an incarnation of the main setup: “The Game” and “The Room”. They all share objectives and methodologies, but based on each project’s main focus, there are slight variations.

The Controller and Visitor play a collaborative game. The Visitor interacts with a mobile robot in the real world while the Controller plays a game in VR, unknowingly controlling the robot in the physical space in real time. They both find themselves in a maze, and they have to escape it in a short time.

Either one is privy to information that the other requires, but only the other player can actually perform actions required to win. To each user, the other is an unfamiliar alien. Moreover, the two cannot speak: they must communicate non-verbally, and they will need to learn how to cooperate to escape. With this project we push the boundaries of communication, driving the users to the extreme with a time limit objective.

The Visitor enters a closed space, a room, and finds it to be an entire abstract living organism. A space that has come to life. This space is none other than the avatar that the Controller is embodying. This research pushes the boundaries of interaction itself. Notions of gaze, body, personal distance, attention, they are all disrupted, as these two beings find themselves one inside the other. What kind of interaction is possible in such a condition? How can a space be alive?

In “the Game”, since more familiar creatures are created than in “The Room”, the main objective is to study whether the specific robot designs (shape, movement, but also control and sensory perception systems) are capable of allowing human subjects to interact within the specific contexts that are given to them. For example, are the human subject able to complete together and escape room that requires them to instantiate an emergent communication, to exchange specific types of information according to our game design? Are they feeling empathy for these other creatures they are interacting with?

Thus, the subject’s motivations are quite structured during “the Game”, and the main research question is whether our expectations are met, with respect to the quality of our system and its ability to allow the interaction to unfold according to this structure. And also, if this is not the case, to what extent the subjects deviate from this structure, and when.

In this track we ask ourselves if the human subjects are able to instantiate an emergent communication, to exchange specific types of information. As this is necessary to complete the game, the amount of victories quantifies the quality of the setup.

The first complete experiment of The Game is structured as a two-player interactive installation, “The Maze”. Each player is told there are two separate experiences, and will try them both.

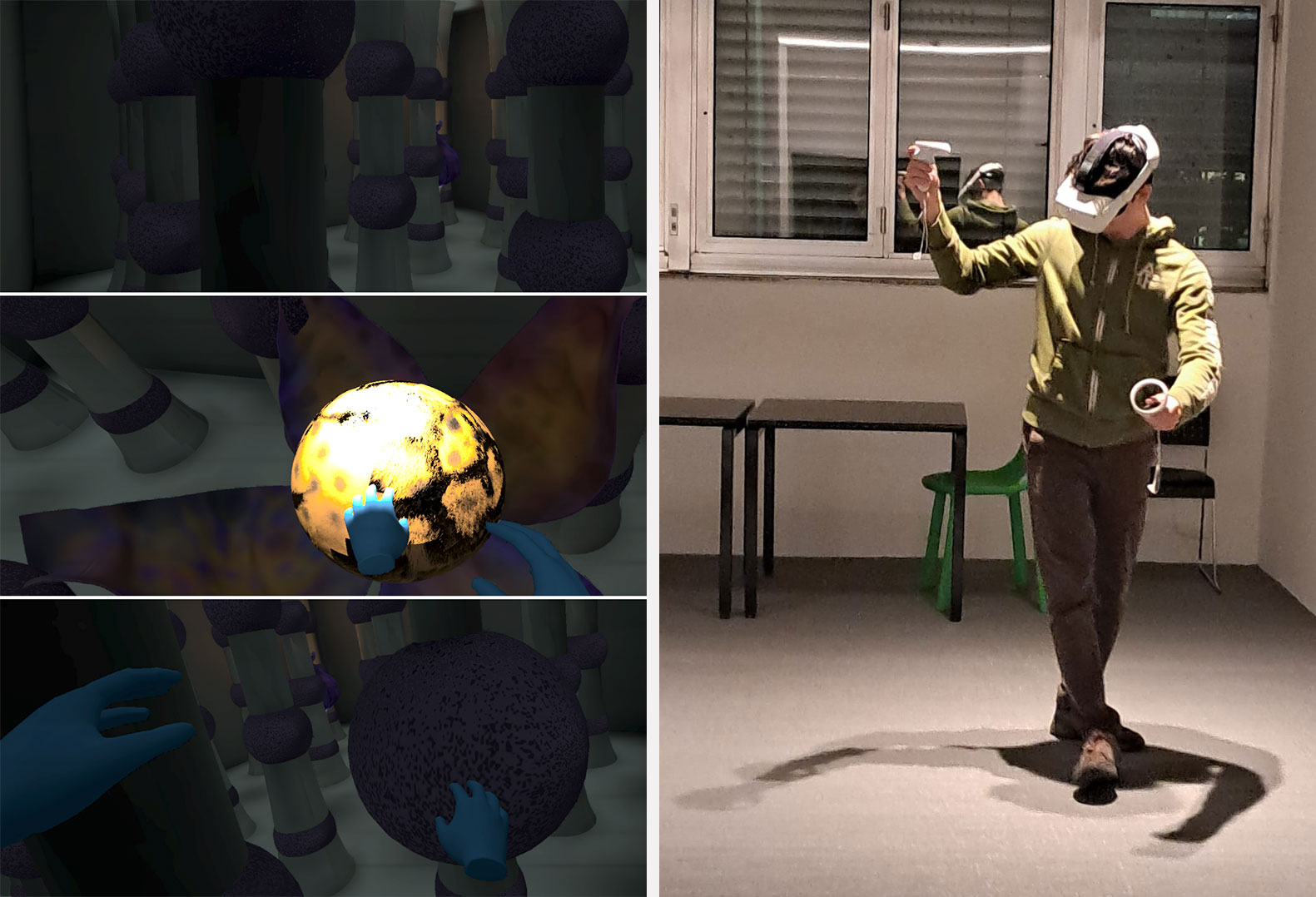

On the Visitor side (Fig. 2, top), they enter a physical escape room with 5 white “stations” and a mobile robot. They are explained the rules: victory is obtained if all of the green stations are activated before the time limit (10 minutes) expires. Crucially, they cannot perform this action, only the robot can. Therefore, their task is to teach the robot how to play, non-verbally.

On the Controller side (Fig. 2, bottom), it is a minimalistic escape room in VR. They are told nothing, just that they need to “understand how to escape” within a time limit. They will encounter an alien in the virtual space, and they will need to interpret what the alien is trying to communicate to them.

The focus of this phase is on the experience of the user interacting with the robot in the real world, and on the design of the sensory translation system and the expressive capability of the human translations on the Controller side. The Game is tested with both test users as the Visitor and the Controller, with no trained operator in the loop. The first version of the project was presented at the Milano Digital Week 2023 and xCities exposition within Politecnico di Milano in Fall 2023.

Fig. 2. “The Game” installation at xCities exposition at Politecnico di Milano. Top: the Visitor, tasked to try to make “the robot” (actually, the Controller, in the other room) understand the game before time expires, only through non-verbal communication; Bottom: the Controller. The participant unknowingly controls a robot in the other room, and its VR environment is a translation of the robot’s perception in real time. This includes “the alien”, the representation of the Visitor currently interacting with the robot.

On the design of the virtual world, two aspects needed to be addressed.

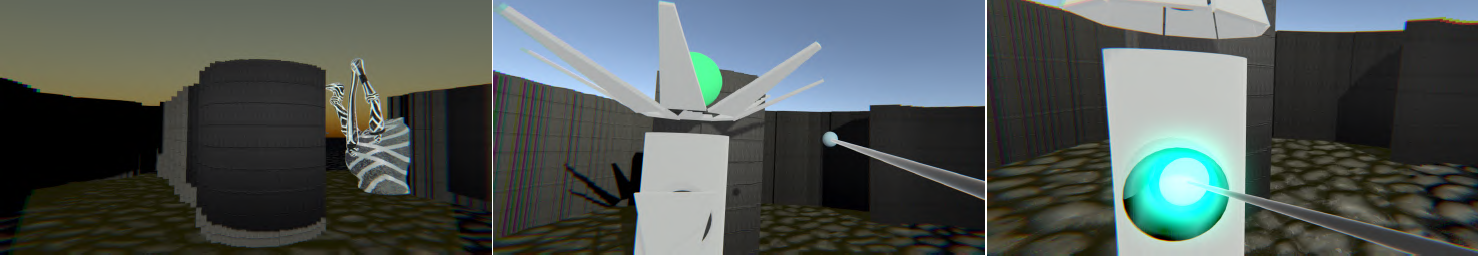

The first is the design of the environment itself, in term of its affordances (Fig. 3). In embodying the robot, the human body and all its capabilities are translated in an avatar that can only move in space on a place, and interact with the stations. Thus, any type of obstacle and limit is translated into a minimal dark wall, which just needed to represent “limit” in the navigation, and the stations aesthetic highlights them against the minimal world, and they could be activated with a cursor attached to the player hand. The robot avatar could also “look around”. The movement of the camera head of the physical robot moved together with the head movement of the Controller.

Fig. 3. “The Game” design of the virtual environment. Left: obstacles as minimal walls. Center: design of the stations and cursor. Right: station interaction mechanism

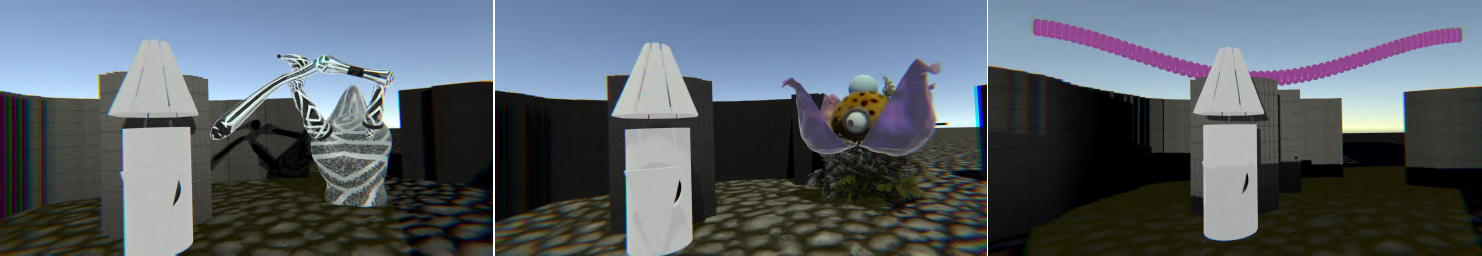

The second is the design of the “human translation” (Fig. 4). The Visitor in the real world is translated into different “alien otherness” in the virtual environment of the controller, with increasing level of non-anthropomorphism. The first is Odile, having both an arm and a head. The second is Siid, having petals in place of the arms and a single eye instead of a face. Finally, the most abstract representation is the Evangelion, a wave in the sky translating information of the relative position of Visitor and robot into characteristics of the shape (color, frequency, thickness, amplitude). For each experience, one of the three representations is chosen at random and maintained throughout the game. We investigate whether these radically different representations of the same information (the Visitor behavior) impact the possibility to establish a communication mechanism between Visitor and Controller.

Fig. 4. “The Game” design of the human translation. Left: Odile, with one arm and face. Center: Siid, with petals and eye. Right: Evangelion, a wave in the sky

Results are obtained from an anonymous questionnaire with both open and closed questions, from the observation of the participants behavior and from informal discussions at the end of the experiences.

The main result is the victory rate for the three different human representations. For Odile, the most anthropomorphic, is 48%. For Siid, 47% and for Evangelion is 33%. Though they may not seem very high, they are a significant result, proving that emergent communication mechanisms can be established even in such stringent conditions and short time between complete strangers with no previous knowledge.

Evangelion the wave in the sky opened up new questions about the meaning of otherness, as its shape was perceived as part of the environment and changed the perception of the game, while at the same time eliciting in the Controller a desire to communicate with it higher than for the other aliens and increased the enjoyment of the experience despite the lower success rate.

68% of participants on the Controller side agreed that there was “another living being” in the space, and that they wanted to communicate with them but only 25% felt they were able to do so. This is understandable, since the experience was designed for the Visitor to communicate with the Controller and not the other way around.

On the Visitor side, they felt they understood what the robot was doing, and perceived as “trying to learn”. They felt the desire to communicate but observing their behavior they mostly used their arms to do so, but only Odile clearly mapped arms movement, which could account for the higher victory rate for that representation. Mainly, the winners were those participants that used their position and face orientation to guide the robot, developing a “follow me” strategy.

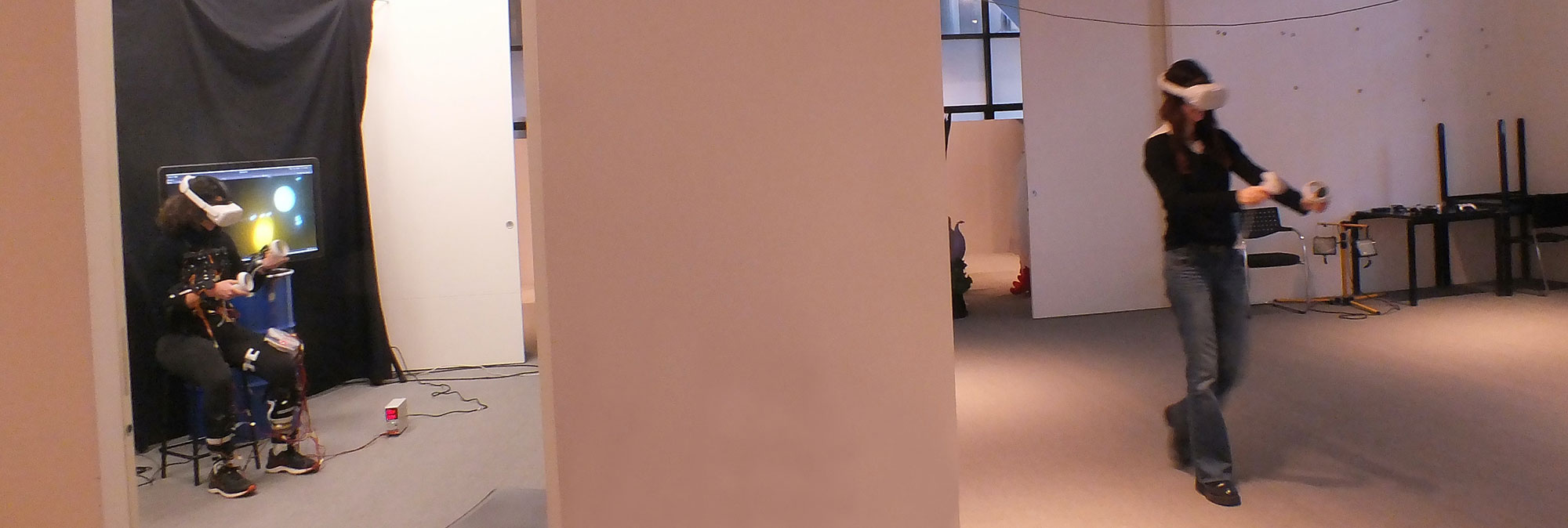

“The Room” (Fig. 5) is an even more challenging project because it places participants in a more demanding situation. Not only is the body of a room completely unfamiliar as a social being, 'this alternate environment also introduces a completely new pattern to the nature itself of the interaction in which communication needs to be rebuilt from the ground up.

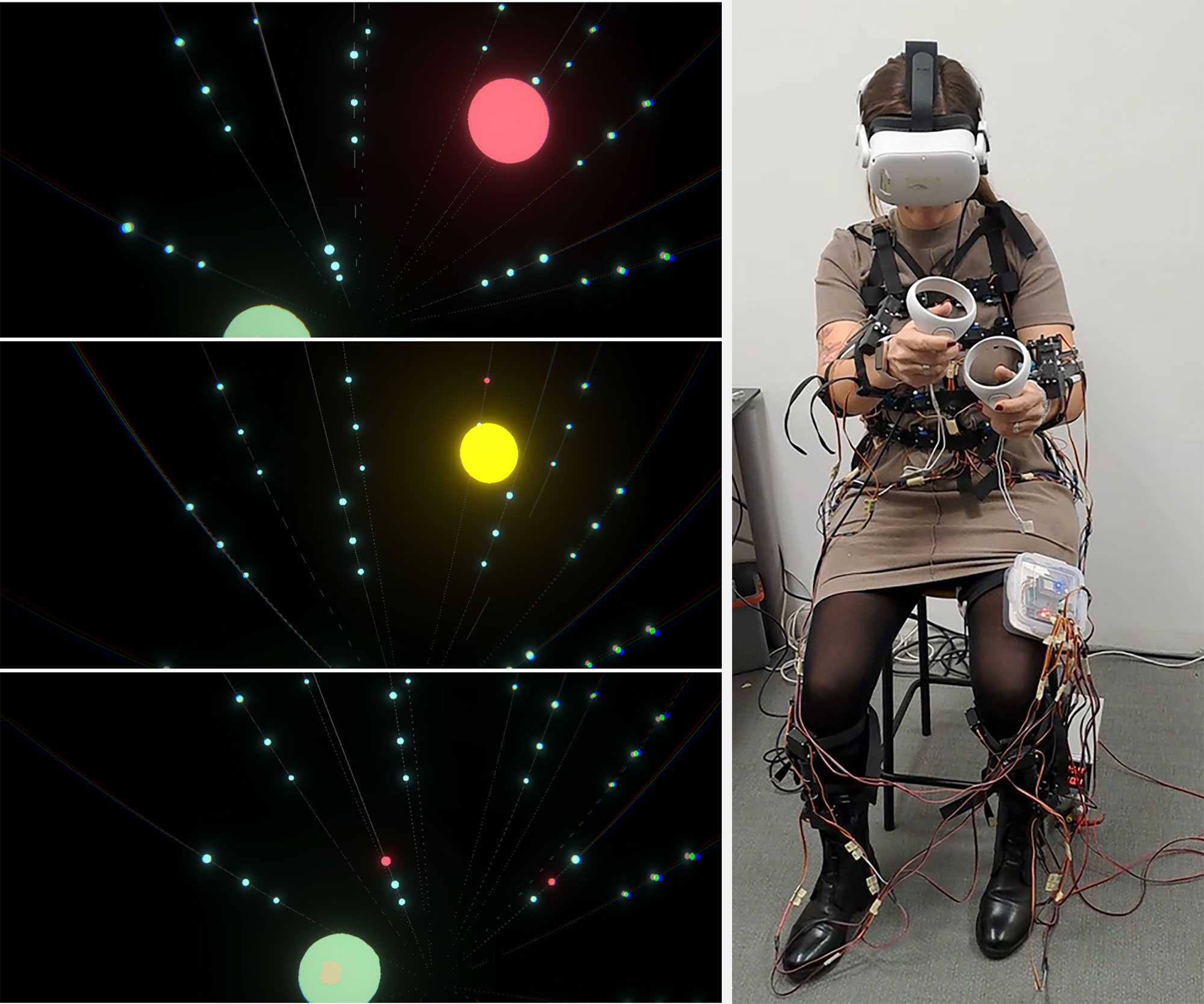

Fig. 5. Participants interacting within “The Room” installation.

Conceptually, the setup is the same as for “The Game”, with two humans interacting through a digital filter: a Controller subject embodying a highly non-anthropomorphic avatar, and a Visitor subject interacting with this avatar in the same shared space. The core of the Room project is in the nature of the avatar: an enclosed space, designed to be an organic living being. In this context, it is not possible to start, as it is done in “The Game”, from specific motivations and structures for the characters involved in the interaction, namely, the Controller, embodying the Room, and the Visitor, that goes inside it.

In “The Game”, the two participants had clear motives and clear goals, a clear narrative. This could work because the context of interaction, even if the creature is new and strange, is still to some extent familiar and recognizable. With “The Room”, there is no initial, clear narrative designed from the start. The main point itself is to understand how an actuated space could become a social being, believable, authentic. Which could be its motivations? Its drives? And the same holds for the Visitor, entering the Room. Thus, the main objective of “The Room” project is to build the Room as a character, to understand how it could be an authentic other.

The Room is so radically different as an avatar from existing research that no valuable information was previously available from embodiment theory and results. Instead, to start building a framework to guide the design of The Room, we made a thorough review of theories on how humans interact with spaces (the Room IS a space), and on spaces as interactive installations. As a result, an initial framework was designed on the possible elements that could compose the Room, how the room could “express itself”, and what types of interaction mechanism with the visitor are designed for it.

Immediately after the framework was formulated, we designed a pilot study to test a subset of its elements, an experiment in the form of an interactive installation, displayed at the xCities expositions within Politecnico di Milano in Fall 2023.

This pilot experiment focused on the experience of the Controller, embodying the Room avatar (Fig. 6). As the Room has no concept of face (a precise location as the focus of interaction), the objective was to design a sensory translation that was less pervasive on the vision side, and that instead focused on haptic sensations: coherently with the Room being a “distributed body”, the human sense that most closely resembles it is touch. Thus, four different haptic devices have been developed, with the sensations of tightening, sliding over the skin with either a pleasurable of bad sensation, push, and point touches. On the visual channel, they experienced a minimal world in VR, corresponding to actions and feedback from the Room body.

On the Visitor side (Fig. 7), the subject could enter The Room as a space in virtual reality. A space of inflatable columns they could interact with and explore.

The participants were not told the two experiences were connected. The Visitor was left to freely explore with no task, while we gave the Controller a task within the minimal VR world they could perceive, without explicitly telling them what it corresponded to. As a “social need” for the Room, the driver of interaction, we gave them the task of “turning the flow (an element of their VR world) pink”. Actually, this corresponded to the Visitor caressing the giant flower in the Room, and it would also result in pleasurable haptic sensations for the Controller. However, if the touch was too rough, they would get a displeasing sensation.

On both sides, we had a strong positive feedback on enjoyment of the experience, and a very high level of immersion.

On the Controller side, the haptic devices were praised for being comfortable to wear, and for providing clearly recognizable different sensations. However, the reported presence of “another living being” was very low, possibly due to the minimality of the virtual environment.

On the Visitor side, the environment was reported to be intriguing and fostered exploration. However, engagement would often decline due to a “negative interaction loop”: the responsiveness of each side of the experience depended on the other participant’s actions. As one of them slows its responses, the other participant’s side will be less active, less interesting, and lead to less actions. And the spiral goes on. The minimality of the environment on the Controller side led the often to be the first step in this loop.

Fig. 6. “The Room” installation: The Controller. On the left, the Controller’s view in VR. On the right, the Controller itself, wearing the haptic feedback devices we developed that translate the virtual signals into an embodied experience. The Controller can touch, with its hands represented as yellow globes, the small spheres to inflate them, and touch the flower bud to open it. A red sphere indicates that the Visitor is touching the corresponding sphere on its side.

Fig. 7. “The Room” installation: The Visitor. On the left, the Visitor’s view in VR, representing the Room itself. On the right, the Visitor itself. The Visitor enters the digital room, with columns and the flower that the Controller can open. The purple spheres set in the columns are the elements that the Controller can inflate and that turn red on its side if touched by the Visitor. All these actions trigger the corresponding haptic devices worn by the Controller.

With this paper I introduce the current state of my PhD research, “First Contact”, an investigation on embodiment and interaction with highly non-anthropomorphic avatars, and I show the two pilot projects in which it is articulated.

The first project, The Game, focuses on more “classically” non-anthropomorphic avatars, social robots. Due to the presence of rich background on human-robot interaction, the novelty of this track is in the creation of advanced interaction contexts, in the form of collaborative games. Results showed that despite the complexity of the digital filter, the system is still able to foster the perception of otherness, and in allowing participants to formulate a shared communication language and to be able to complete tasks together. Further research is needed to increase the possibility of mutual understanding in two-way communication tasks.

The second project, The Room, introduces the concept of spaces as living, organic beings, the avatar themselves, investigating the possibility to design the Room as a believable character, its embodiment, and social drives. A pilot experiment was designed focusing on minimal visual perception on the Controller side leveraging more haptic sensations instead. Results show that while immersion was high, the perception of otherness was low, possibly due to the abstract nature of the feedback on the Controller side that also led to decrease action, and thus interaction, between the subjects. Further research is needed to understand how such an avatar can be more naturally embodied, to drive the Controller into action and feeling more clearly the social needs of the Room.