In the age of Artificial Intelligence (AI), where algorithms significantly influence the representation and perception of human bodies online, this research investigates the complex interplay between AI technologies and digital aesthetics. AI systems, particularly neural networks, are pervasive in shaping beauty standards and self-perception through their integration into social media and other digital platforms. By examining AI’s impact on human body aesthetics, the study employs Don Ihde’s theory of human-technology interactions, focusing on embodiment, hermeneutic, and alterity relations. It reveals how AI algorithms act as extensions of the body, transform body image through beauty filters, mediate aesthetic norms via content moderation, and generate idealised body representations. The research also critiques the role of AI in perpetuating biased beauty ideals, often reflective of Western-centric views, and emphasises the need for a decolonized perspective in understanding beauty standards. The findings highlight how AI influences both the creative process and societal norms, raising ethical concerns about autonomy, representation, and the impact of digital technologies on artistic expression and cultural diversity.

Artificial Intelligence, Aesthetics, Visual Arts, Deep Learning, Computer Vision, Beauty Filters, Censorship.

We live in an era dominated by advanced Artificial Intelligence (AI), where data and algorithms shape the flow of goods, services, images, and messages (Russell, 2016). AI technologies, especially neural networks, process vast amounts of data, making digital computation feel more concrete and integral to our daily lives (Goodfellow et al., 2016).

As AI systems become more widespread, especially in the digital world, it becomes harder to question their results on our culture, as their interpretations are blending with our own, making it difficult to separate our experiences from their influence (Barrat, 2023). In this work, we specifically investigate how AI algorithms influence the representation and perception of human bodies in the digital world. Focusing on how these technologies shape human aesthetics in digital environments and social media by dictating standards and norms, we claim that AI not only affects self-perception and societal values but also extends its influence into visual arts, redefining beauty, representation, and creativity. Our aim is to critically examine these impacts and explore the broader consequences of AI's role in shaping human aesthetics.

To grasp the complex dynamics that this work wishes to investigate, we consider an interesting cinema reference cited by Henry Jenkins in his famous theory of “Media Convergence” (Jenkins, 2004). In this work, the author observes that in the ending of The Truman Show, it is quite hard to imagine that Truman might choose to remain within the “media” and exploit it for his own purposes. He decides, instead, to go and see the “real” world, and both us as public and the meta-public in the movie empathise with this choice. In this movie, the protagonist lives an ordinary life in a seemingly perfect town, unaware that his entire existence is a crafted reality TV show broadcasted to the world. Truman’s every move is monitored and controlled by the show's director, who manipulates Truman's environment to maintain the illusion. The film ends with Truman discovering the truth and choosing to leave the artificial world behind.

This scenario is in contrast with contemporary trends, where individuals actively share their personal values, narratives, and images online, being an active part of the visual culture (Jenkins, 2004). Big tech companies control the development of digital technologies, functioning as mediating entities that control the mechanisms of content creation and distribution online (Cohen, 2019). Their operations are heavily reliant on AI, leading to significant implications for all aspects of our existence online and offline, including the representation and perception of human bodies. As users, we are participants in a system where our interactions are guided by unseen forces that prioritise certain narratives over others, reinforcing specific ideals and standards. This mediated environment raises critical questions about autonomy, agency, and the true nature of participation in the digital age.

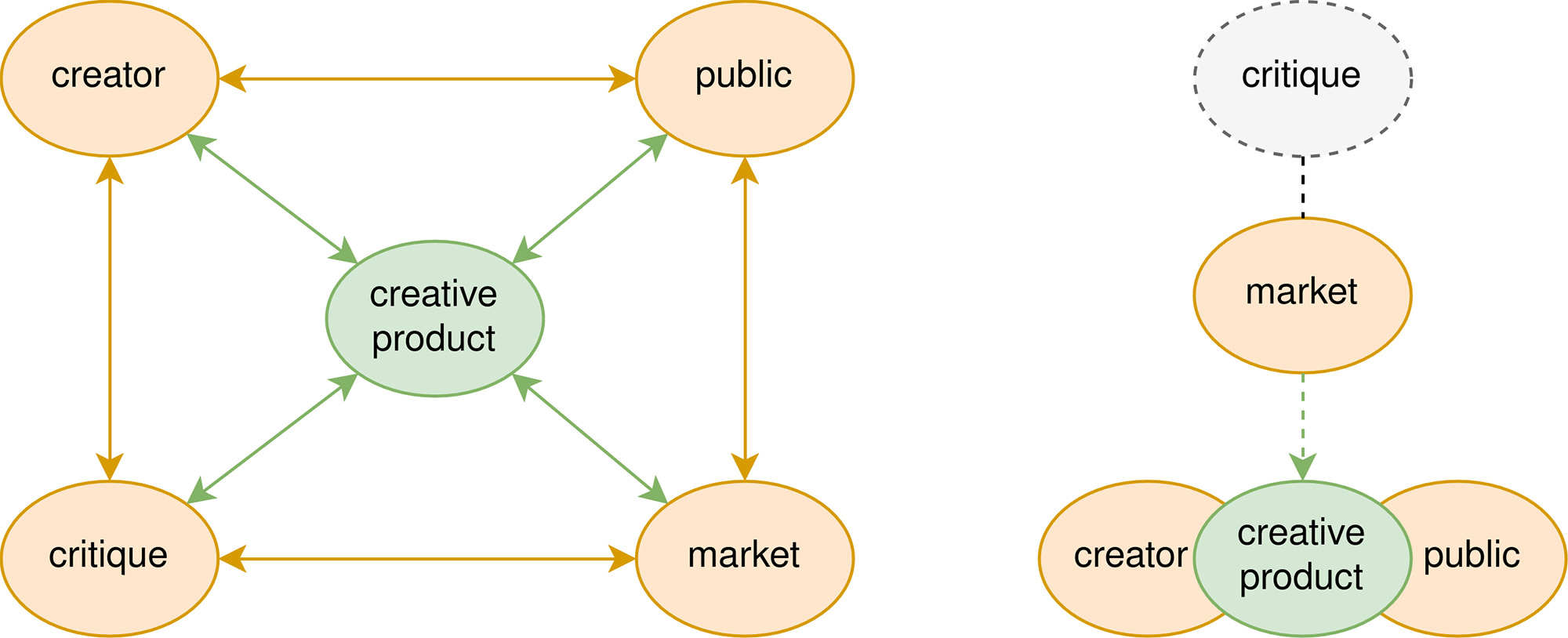

Considering specifically the creative environment in the digital world, we draw a parallel between other historical periods and ours (Riccio et al., 2022a), focusing on four main actors: critique/theory, market, public/observer, and creators. As illustrated in Figure 1, we argue that, historically, these elements have been organised in a non-hierarchical structure. Depending on the artistic movement and historical period, one element (such as critique/theory) might have held more prominence than others in shaping the creative environment (Montaner, 1999). Studies in art history delineate the connections and relations between these elements and develop discourses about artistic production from various disciplinary perspectives, including philosophy, morality, religion, politics, economics, and aesthetics. In today's context, these elements play new roles: the public is not merely a consumer but may also become the product and the creation. Furthermore, AI algorithms function both as creators and as critics in an opaque manner. This dual role of AI introduces complexities in the creative process, as algorithms can both influence and be influenced by prevailing cultural norms and market demands. The opacity of AI's decision-making processes adds another layer of challenge, making it difficult to discern the underlying biases and assumptions that guide these algorithms.

Fig. 1. Synthetic sketch of the key elements within the creative ecosystem. Left, non-hierarchical arrangement among these elements before the advent of social media and AI; Right, transformation of the relationships in the context of AI algorithms used on social media.

In the context of the creative landscape that we have defined, we specifically analyse how the interaction between AI and humans becomes an important mediating element to understand the representation of human bodies. To perform this analysis, we ground our work in the theory of interactions between technologies and humans provided by Don Ihde (Ihde, 1990). Considering AI in the digital world becoming a mediator of the representation of human bodies via embodiment, hermeneutic and alterity relations, we provide an overview of three different paradigms in which AI is influencing the human body aesthetics in the digital world.

Embodiment Relations: Ihde examines how technology extends and transforms the human body. Technologies become part of our bodily experience, changing how we perceive and interact with the world. In this context, AI algorithms, used in beauty filters and body modification apps, can be seen as extensions of the body. They alter how users perceive their own bodies and how they present themselves to others, directly impacting self-image and body representation.

Hermeneutic Relations: Ihde discusses how technologies act as interpretative frameworks, mediating our understanding of the world. These technologies provide "lenses" through which we interpret various phenomena. Similarly, AI algorithms on social media serve as hermeneutic tools that interpret and evaluate body images. Through content moderation and recommendation systems, AI shapes societal norms and standards of beauty, influencing how individuals and communities perceive body representations.

Alterity Relations: Ihde explores the concept of technology as a quasi-other, an entity that we interact with as if it were an autonomous agent. This interaction shapes our experiences and perceptions. AI-driven virtual assistants, chatbots, and generative AI systems can be viewed as alterity relations. These AI entities influence users' perceptions and decisions regarding body image and representation, creating new forms of interaction and self-perception.

In the next paragraphs, we further develop our discussion in these fields, highlighting the empirical results that we have obtained in our research.

Selfies have become a ubiquitous form of self-expression on platforms like Instagram, Snapchat, and TikTok. This trend, as highlighted by Bruno et al. (2018), positions selfies as a distinct visual medium that underscores self-presentation aligned with societal norms and the pursuit of positive validation (Goffman et al., 1978). In the context of embodiment relations, AI-powered beauty filters, leveraging advancements in computer vision, recognize facial features and apply augmented reality (AR) enhancements or alterations to users' faces in real-time (Rios, 2018). Initially, selfies served as digital representations of individuals' physical existence (Hess, 2015). However, the integration of these filters blurs the lines between online identity and digital artefacts, transforming how users experience and present their bodies.

By creating two innovative datasets that apply eight popular beauty filters to public collections of faces, we gain insights into the effects of these filters on original facial images. These filters homogenise facial aesthetics while preserving individual identities, without significantly impacting state-of-the-art face recognition models (Riccio et al., 2022b). The proposed pipeline to beautify the images is provided in Figure 2.

Fig. 2. Sketch representing our pipeline (OpenFilter) developed and employed to beautify existing public collections of faces

The availability of our beautified datasets allows us to examine the aesthetic standards propagated by this technology, particularly regarding racial biases (Riccio and Oliver, 2022). We used deep learning to demonstrate that beauty filters tend to make individuals from different races appear whiter. Through Explainable AI techniques, we found that this bias extends beyond skin colour alterations to include modifications of facial features. This underscores how AI technologies, as extensions of the body, mediate and transform our perceptions and representations of ourselves in ways that reflect and reinforce societal biases (Riccio et al., 2024a).

On social media platforms, AI algorithms are used to automatically identify and manage content that violates community guidelines, leading to removal or shadow-banning (deprioritization). Given that social media are crucial tools for contemporary artists to showcase their work, reach a wider audience, and enhance their visibility (Polaine et al., 2005), algorithmic content moderation significantly impacts artistic expressions and body representation in contemporary digital arts. This often results in controversial instances where artistic content is removed, banned, or deprioritized due to factors like political undertones, copyright infringements, or depictions of nudity (Gillespie, 2020). These actions directly affect the creative freedom of artists and can lead to considerable economic losses. The examination of this phenomenon extends beyond understanding our cultural landscape to address ethical concerns regarding artistic freedom and creators' rights.

From a hermeneutic perspective, AI algorithms act as interpretative frameworks that influence how artistic content is perceived and categorised. The automatic detection of inappropriate nudity presents significant challenges, as the distinction between artistic nudity and pornography is often ambiguous, context-dependent, and influenced by the artist's intention (Vasilaki, 2013; Partridge, 2013; Eck, 2001). This area has received limited attention in technical scientific communities, despite significantly impacting not only individual artists but also cultural institutions and societal values (Lidquist, 2017). Historically, artistic nudity has been a powerful form of self-expression and a reflection of societal norms, influencing cultural understanding and challenging conventions (Bonfante, 1989). However, the current trend of censoring such art on digital platforms undermines artistic freedom and may deter younger artists from exploring nudity in their work (Riccio et al., 2024b). This censorship also contributes to a homogenising effect on creative expression and threatens democratic values by restricting access to diverse artistic voices (Gagnon, 2020). Moreover, labelling nudity as harmful reinforces negative perceptions of the human body, which can adversely affect individuals' body image and limit crucial educational and health-related discourse (Sciberras and Tanner, 2023). Although content moderation is essential for maintaining a safe digital environment, artistic nudity warrants special consideration to preserve its cultural and educational significance (Riccio et al., 2024b).

From the perspective of alterity relations, diffusion models and other visual generative AI tools represent a significant shift in how human bodies and aesthetics are created and perceived (Foster, 2019). These AI technologies function as quasi-other entities, actively generating and modifying images of human bodies that go beyond mere replication of reality. By creating highly realistic and often idealised representations, these tools influence societal standards of beauty and body image. For instance, generative AI can produce new images that adhere to prevailing beauty norms, altering facial features, body shapes, and skin tones to fit idealised standards (Luccioni, 2023). This process positions AI as an interactive agent that not only reflects but also shapes user perceptions of beauty and identity.

These AI-generated images are then disseminated across social media platforms, further entrenching certain aesthetic ideals and influencing how individuals perceive their own bodies and those of others (Manovich, 2017). The role of these AI tools as quasi-others raises critical ethical and social questions about the autonomy of human self-representation, the reinforcement of potentially harmful beauty standards, and the implications for body diversity and acceptance. By mediating and transforming body aesthetics, generative AI technologies significantly impact the way we relate to our own bodies and to each other, highlighting the profound influence of these digital entities in contemporary visual culture.

The pervasive integration of AI in the digital environment inevitably imposes judgments on the representation of the human body, as metaphorically depicted by the role of AI as “critique” in Figure 1. Indexical AI systems (Weatherby and Justie), which rely on contextual data to make decisions, have the potential of continuously shaping and redefining how bodies are perceived and presented online. By applying contextual and referential data, these AI systems can interpret and transform body images according to specific societal norms and aesthetic standards. AI's omnipresence in digital spaces means that our understanding and representation of the human body are constantly being mediated by these systems, underscoring the profound impact of AI on our visual and cultural landscapes, as it continuously evaluates and reshapes body aesthetics and norms through its embedded judgments (Noble, 2019).

The fact that these technologies are mostly developed and deployed in the global North shifts the type of influence and direction taken by their decisions. For example, the widespread adoption of beauty filters and the global dissemination of standardised — yet biased — beauty ideals represented by these filters can be viewed through the lens of globalisation, which some scholars consider a contemporary form of colonisation (Banerjee et al., 2001), often referred to as "electronic colonisation" (Zembylas and Charalambos, 2005). As a predominantly Western-driven process, globalisation tends to portray the Western world as desirable and advantageous while appropriating, homogenising, and standardising cultures from the Global South (Akinro and Mbunyuza-Memani, 2019). Our research contributes to an empirical, and data-driven understanding of the standardisation of beauty ideals perpetuated by this modern colonisation phenomenon. Thus, we believe that the phenomenon of beauty filters should be studied with a decolonisation perspective, acknowledging historical colonial legacies, advocating for cultural appreciation over appropriation, promoting inclusive beauty standards, and empowering diverse communities to reclaim their narratives and beauty canons. In this context, we also emphasise that according to Dobson (2015), the adoption of beauty filters contributes to the objectification of women, while Elias and Gill (2018) argue that the underlying aesthetic ideology of beauty filters perpetuates conventional ideals of femininity, thereby narrowing the representation of female faces towards normative beauty standards. Considering the extensive prevalence of beauty filters, they represent an intriguing area of research that can enrich our comprehension of the evolution of modern culture and aesthetics (Shein, 2021).

The inclusion of gender norms in technological development is also evident in the utilisation of AI for content moderation practices. Seen from a techno feminist perspective (Riccio and Oliver, 2024), it is indeed the case that feminist artists are censored more than others and that representation of female bodies tend to be more oversexualized than their male counterparts (Witt et al., 2019). In addition, the regulation itself of artistic nudity on online platforms highlights a complex intersection between censorship and creative expression. While general content moderation deals with everyday user-generated posts, artistic content faces specific challenges, often subjected to stricter scrutiny under the guise of moral protection. From a mere technical perspective, it is clear that the difficulty in distinguishing between artistic and pornographic nudity is a result of lack of contextualization and excessive literalization of contemporary content moderation practices (Leung, 2022). Content creators may align with platform dynamics for commercial gain, but artists frequently seek to push boundaries and question societal norms. Art history is indeed full of examples of artworks born from transgression against moral norms. Unfortunately, AI algorithms possess the potential not only to influence a single link in the diagram depicted in Figure 1 but also to simultaneously impact all elements within the creative environment (Kulesz, 2018). As a consequence, the traditional non-hierarchical structure evolves into a hierarchical organisation where the Market assumes the highest position, serving as the ultimate driver of the creative process. The digital world emerges as a quasi-monopoly for cultural production, delineating more distinct yet invisible boundaries between what is considered acceptable and what is not, what is beautiful and what is not. In such a binary environment, the act of challenging aesthetic, moral and artistic norms becomes increasingly challenging.

The integration of AI into digital environments profoundly reshapes how human bodies are represented and perceived. This research underscores the dual role of AI as both a mediator and critique in aesthetic standards, highlighting its impact on self-perception, artistic expression, and societal norms. The findings point to a critical need for greater transparency and inclusivity in AI systems, advocating for a decolonized approach to beauty standards that respects and celebrates diverse cultural expressions. The study also calls attention to the ethical implications of AI's pervasive influence, particularly regarding the potential reinforcement of existing biases and the restriction of creative freedom. As AI continues to play a central role in digital culture, it is imperative to address these challenges and strive for a more equitable and nuanced understanding of how technology shapes human aesthetics and creative expression.

PR is supported by a nominal grant received at the ELLIS Unit Alicante Foundation from the Regional Government of Valencia in Spain (Convenio Singular signed with Generalitat Valenciana, Conselleria de Innovación, Industria, Comercio y Turismo, Dirección General de Innovación). PR is also supported by a grant by the Bank Sabadell Foundation.

Akinro, Ngozi, and Lindani Mbunyuza-Memani. 2019. Black Is Not Beautiful: Persistent Messages and the Globalization of “White” Beauty in African Women’s Magazines. Journal of International and Intercultural Communication 12, no. 4: 308–24.

Banerjee, Subhabrata Bobby, and Stephen Linstead. 2001. Globalization, Multiculturalism and Other Fictions: Colonialism for the New Millennium? Organization 8, no. 4: 683–722.

Barrat, J. 2023. Our final invention: Artificial intelligence and the end of the human era. Hachette UK.

Bonfante, Larissa. 1989. Nudity as a costume in classical art. American Journal of Archaeology 93.4: 543-570.

Bruno, Nicola, Katarzyna Pisanski, Agnieszka Sorokowska, and Piotr Sorokowski. 2018. Editorial: Understanding Selfies. Frontiers in Psychology 9: 44.

Cohen, Julie E. 2019. The age of surveillance capitalism: The fight for a human future at the new frontier of power. Surveillance & Society 17.1/2: 240-245.

Dobson, Amy Rose Shields. 2015. Postfeminist Digital Cultures: Femininity, Social Media, and

Self-Representation. Palgrave Macmillan.

Eck, Beth A. 2001. Nudity and Framing: Classifying Art, Pornography, Information, and Ambiguity. Sociological Forum, 16:603–32. Springer.

Elias, Ana Sofia, and Rosalind Gill. 2018. Beauty Surveillance: The Digital Self-Monitoring Cultures of Neoliberalism. European Journal of Cultural Studies 21, no. 1: 59–77.

Foster, David. 2019. Generative deep learning: teaching machines to paint. Write, Compose, and Play

(Japanese Version) O’Reilly Media Incorporated: 139-140.

Gagnon, Gabrielle. 2020. One-dimensional body: The homogenized body of Instagram's# BodyPositive.

Gillespie, Tarleton. 2020. Content Moderation, AI, and the Question of Scale. Big Data & Society 7, no. 2: 2053951720943234.

Goffman, Erving, and Others. 1978. The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life. Harmondsworth London.

Goodfellow, Ian, Yoshua Bengio, and Aaron Courville. 2016. Deep learning. MIT press.

Hedman, Pontus, Vasilios Skepetzis, Kevin Hernandez-Diaz, Josef Bigun, and Fernando Alonso-Fernandez. 2022. LFW-Beautified: A Dataset of Face Images with Beautification and Augmented Reality Filters. arXiv:2203. 06082.

Hess, A. 2015. The Selfie Assemblage. International Journal of Communication 9, no. 1: 1629–46.

Huang, Gary B., Marwan Mattar, Tamara Berg, and Eric Learned-Miller. 2008. Labeled Faces in the Wild: A Database for Studying Face Recognition in Unconstrained Environments. Workshop on Faces in ‘Real-Life’ Images: Detection, Alignment, and Recognition.

Ihde, Don. 1990. Technology and the lifeworld: From garden to earth. Indiana University Press.

Jenkins, Henry. 2004. The cultural logic of media convergence. International journal of cultural studies 7.1: 33-43.

Karkkainen, Kimmo, and Jungseock Joo. 2021. FairFace: Face Attribute Dataset for Balanced Race, Gender, and Age for Bias Measurement and Mitigation. IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV), 1548–58.

Kulesz, Octavio. 2018. Culture, Platforms and Machines: The Impact of Artificial Intelligence on the Diversity of Cultural Expressions. Intergovernmental Committee for the Protection and Promotion of the Diversity of Cultural Expressions, 2018.

Manovich, Lev. 2017. Automating aesthetics: Artificial intelligence and image culture. Flash Art International 316: 1-10.

Montaner, J. M. 1999. Arquitectura y Crítica. Gustavo Gili.

Noble, Safiya Umoja. 2018. Algorithms of oppression: How search engines reinforce racism. Algorithms of oppression. New York university press.

Patridge, Stephanie. 2013. Exclusivism and Evaluation: Art, Erotica and Pornography. Pornographic Art and the Aesthetics of Pornography, 43–57. Springer.

Polaine, Andrew. 2005. Lowbrow, High Art: Why Big Fine Art Doesn’t Understand Interactivity.

Ramirez, J. A. 1998. Art History and Critique: Faults (and Failures). F. Cesar Manrique.

Riccio, Piera, Jose Luis Oliver, Francisco Escolano, and Nuria Oliver. 2022. Algorithmic Censorship of Art: A Proposed Research Agenda. International Conference on Computational Creativity. (Riccio et al., 2022a)

Riccio, Piera, Bill Psomas, Francesco Galati, Francisco Escolano, Thomas Hofmann, and Nuria Oliver. 2022. OpenFilter: A Framework to Democratize Research Access to Social Media AR Filters. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 35: 12491–503. (Riccio et al. 2022b)

Riccio, Piera, and Nuria Oliver. 2022. Racial Bias in the Beautyverse: Evaluation of Augmented-Reality Beauty Filters. European Conference on Computer Vision, 714–21. Springer, 2022. (Riccio and Oliver, 2022)

Riccio, Piera, Colin, Julien, Ogolla, Shirley, & Oliver, Nuria. 2024. Mirror, Mirror on the Wall, Who Is the Whitest of All? Racial Biases in Social Media Beauty Filters. Social Media+ Society, 10(2), 20563051241239295. (Riccio et al., 2024a)

Riccio, Piera, Hofmann, Thomas, & Oliver, Nuria. 2024. Exposed or Erased: Algorithmic Censorship of Nudity in Art. Proceedings of the CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 1-17). (Riccio et al., 2024b)

Riccio, Piera, and Nuria Oliver. 2024. A technofeminist perspective on the Algorithmic Censorship of Artistic Nudity. From Hype to Reality: AI in the study of Art and Culture, Biblioteca Hertziana: 83.

Rios, Juan Sebastian, Daniel John Ketterer, and Donghee Yvette Wohn. 2018. How Users Choose a Face Lens on Snapchat. ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work and Social Computing (CSCW), 321–24.

Russell, Stuart J., and Peter Norvig. 2016. Artificial intelligence: a modern approach. Pearson.

Sciberras, Ruby, and Claire Tanner. 2023. Feminist sex-positive art on Instagram: reorienting the sexualizing gaze. Feminist Media Studies 23.6: 2696-2711.

Shein, E. 2021. Filtering for Beauty. Communications of the ACM 64, no. 11: 17–19.

Vasilaki, Mimi. 2010. Why Some Pornography May Be Art. Philosophy and Literature 34, no. 1: 228–33.

Weatherby, Leif, and Brian Justie. 2022. Indexical AI. Critical Inquiry 48.2: 381-415.

Witt, Alice, Nicolas Suzor, and Anna Huggins. 2019. The rule of law on Instagram: An evaluation of the moderation of images depicting women's bodies. University of New South Wales Law Journal, The 42.2: 557-596.

Zembylas, Michalinos, and Charalambos Vrasidas. 2005. Globalization, Information and Communication Technologies, and the Prospect of a “Global Village”: Promises of Inclusion or Electronic Colonization? Journal of Curriculum Studies 37, no. 1: 65–83.